ASA Position on Dry Needling

The American Society of Acupuncturists (“ASA”) opposes the illegal and unsafe practice of acupuncture. “Dry needling” is a pseudonym for acupuncture that has been adopted by physical therapists, chiropractors, and other health providers who lack the legal ability to practice acupuncture within their scope of practice. This strategy allows these groups to skirt safety, testing, and certification standards put into place for the practice of acupuncture. Dry Needling is a style of needling treatment within the greater field of acupuncture. The practice of “acupuncture” includes any insertion of an acupuncture needle for a therapeutic purpose. Acupuncture training has always included both traditional and modern medical understandings.

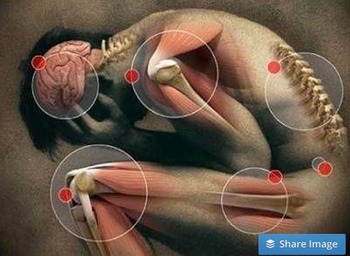

Anatomically, “trigger points” and “acupuncture points” are synonymous, and acupuncture has targeted trigger points for over 2,000 years. “Dry needling” is indistinguishable from acupuncture since it uses the same FDA-regulated medical device specifically defined as an “acupuncture needle,” treats the same anatomical points, and is intended to achieve the same therapeutic purposes as acupuncture.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) defines the acupuncture needle as a Class II medical device, and has explicitly stated that the sale of acupuncture needles “must be clearly restricted to qualified practitioners of acupuncture as determined by the States.” As “dry needling” is acupuncture, it presents the same inherent risks including but not limited to perforation of the lungs and other internal organs, nerve damage, and infection. Recent reports of serious and potentially life-threatening injuries associated with “dry needling” include pneumothoraces and spinal cord injury. These and other injuries support the statement that “dry needling” presents a substantial threat to public safety when performed without adequate education, training, and independent competency examination. Adequate training and competency testing are essential to public safety.

In addition to biomedical training, licensed acupuncturists receive at least 1365 hours of acupuncture-specific training, including 705 hours of acupuncture-specific didactic material and 660 hours of supervised clinical training. Further, many states also require even physicians wishing to practice acupuncture to have substantial training. The American Academy of Medical Acupuncture (AAMA) has set the industry standard for a physician to practice entry level acupuncture at 300 hours of postdoctoral training with passage of an examination by an independent testing board. This standard presumes extensive, pre-requisite training in invasive procedures [including underlying structures, contraindications for skin puncture, clean needle technique, anticipated range of patient responses to invasive technique, etc.], the differential diagnosis of presenting conditions, clinical infection-control procedures in the context of invasive medicine, management of acute office and medical emergencies, and advanced knowledge of human physiology and evidence based medicine. The AAMA expects that physicians choosing to incorporate acupuncture into practice will pursue lifelong learning, including formal and self-directed programs.

In contrast, there are no independent, agency-accredited training programs for “dry needling,” no standardized curriculum, no means of assessing the competence of instructors in the field, and no independently administered competency examinations.

Neither physical therapy nor chiropractic entry-level training includes any meaningful preparation for the practice of invasive therapeutic modalities such as the insertion of acupuncture needles. Training in these programs is generally limited to external therapeutic modalities. In some states, however, physical therapists and others have begun inserting acupuncture needles and practicing acupuncture with 12-24 hours of classroom time and little to no hands-on training or supervision. This is being done under the name “dry needling.”

Physical therapists and chiropractors without acupuncture included in their state practice acts have, in some cases, been authorized to perform dry needling by their own regulatory boards’ non-binding guidelines or through administrative rulemaking. Such actions often occur even when the statutory practice act adopted by the state legislature lacks any legislative intent to authorize invasive procedures such as the insertion of needles.

All health care providers without acupuncture formally included in their state practice act should be prohibited from the practice of acupuncture, even when described as “dry needling,” unless their practice act is legally expanded to include the practice of acupuncture and provide the same level of clinical and classroom training required for the licensure of acupuncturists.

Wednesday, July 19, 2017 at 2:47PM

Wednesday, July 19, 2017 at 2:47PM  [This article is a work in progress]

[This article is a work in progress] Chronic Lymes,

Chronic Lymes,  Lyme,

Lyme,  Lymes,

Lymes,  Lymes disease in

Lymes disease in  Disorders

Disorders